using probability theory to generate wall art

i recently moved into a new apartment and faced the universal problem: empty walls that needed something on them. i wanted art that actually meant something to me. even better if i made it myself. scrolling through twitter, i stumbled on this visualization of a random walk.

a random walk is a concept from probability theory where you take steps in random directions and understand where you end up. what makes it cool is that pure randomness produces patterns that look intentional. i decided to generate my own and print it for my wall (because why not? i am coming for you, van gogh!). but first, let's understand what i was actually making.

what is a random walk?

the concept is simple. start at a point. pick a random direction. take a step. repeat. that's it. no memory of where you've been, no goal of where you're going. just pure and random steps. like a drunk person walking home, or trying to. but despite this simplicity, random walks show up everywhere: pollen grains moving in water (brownian motion), stock prices going up and down, molecules diffusing through gas, animals searching for food.

what makes them work as art is the same thing that makes them useful in physics and finance: individual steps are unpredictable, but the aggregate behavior follows well-defined mathematical laws. you get structure from randomness. patterns emerge without apparent design.

understanding the math

before generating art, it's important to understand why random walks create the patterns they do. the mathematics explains what makes them visually interesting and why they stay can actually fill a canvas instead of just going straight away to infinity.

formal definition

a random walk is a sequence of positions \(S_0, S_1, S_2, \ldots\) where each position is the sum of independent random steps:

where \(X_i\) are independent, identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables representing each step. for a simple random walk on the integers, \(X_i \in \{-1, +1\}\) with equal probability. in higher dimensions, \(X_i \in \mathbb{R}^d\) with some distribution (often uniform on the unit sphere or a Gaussian).

why 2D works for wall art

dimension matters more than you'd think. pólya's recurrence theorem says that in 2D, a random walk will eventually return to its starting point with probability 1. you're guaranteed to come back home. but in 3D and higher, there's a positive probability you'll wander off forever and never return.

this is why 2D random walks make good wall art. the path keeps going back to areas near the origin, creating patterns that fill a bounded space. in 3D, the walk would escape and you'd get sparse, disconnected trails.

why the pattern stays contained

how far does a random walk get after \(n\) steps? intuitively, you could think linearly with \(n\). but because steps cancel out, the actual displacement grows much slower. the expected distance from the origin scales as the square root:

this \(\sqrt{n}\) scaling is why the visualization works as wall art. after 10,000 steps, you're only about 100 steps from the origin. this means that the 10,000 steps (or paint strokes) will be most likely to be within that region, since with 2D walks we are guaranteed to return to the origin eventually.

building the generator

understanding the theory is one thing. actually generating the art required solving a different problem: how do you map random walks to colors in a way that produces visually interesting results? the approach i ended up going for on uses five-dimensional integer space (\(\mathbb{Z}^5\)), where two dimensions control the pixel position and three control the color.

the core algorithm

the algorithm starts with a 5D vector \((y, x, c_1, c_2, c_3)\). the first two components determine which pixel to paint, and the last three represent color values in whatever color space you choose. at each iteration, you randomly pick one of the five dimensions, randomly choose a direction (+1 or -1), take a step, and write the current color to that pixel position. after millions of iterations, you've traced a path through both spatial and color space simultaneously.

what makes this work is the modulo operation. each dimension wraps around within its bounds: positions wrap at image edges, colors wrap at their maximum values. the walk is constrained but still explores the entire space. over time, organic flowing patterns emerge as the walker revisits positions with different color states.

crucially, this is still equivalent to a 2D random walk in terms of space filling, not a 5D walk. the three color dimensions are bounded and wrap around, so they don't let the walk escape to infinity. only the two spatial dimensions matter for Pólya's recurrence theorem. the walk is guaranteed to return to every pixel eventually, painting it with different colors each time.

color spaces matter

i implemented multiple color spaces (RGB, OKLCH, HSL, HSV, LAB) because they produce different results. RGB gives you direct control but harsh transitions. OKLCH is perceptually uniform, so color changes feel smooth and natural. HSL lets you sweep through hues while controlling saturation and lightness independently. each color space has its own personality.

the implementation uses an abstract base class pattern, so adding new color spaces is just implementing three methods: single-pixel conversion, batch conversion, and bounds. the core algorithm doesn't know or care which color space you're using. separation of concerns makes it extensible.

making it fast

generating high-quality images requires millions of iterations. at 1080×1440 resolution with 200 million steps, the naive Python implementation would take hours. i tried. once. learned my lesson after a movie session that consisted of a progress bar and some logs scrolling. the solution: Numba JIT compilation. the hot loop gets compiled to machine code, giving a massive speedup. batch random number generation, selective modulo operations, and pre-allocated arrays squeeze out some more performance out of it.

the color conversion happens once at the end, not on every iteration. store raw color values in a buffer, convert the entire thing to RGB after the walk completes. this alone saves millions of expensive conversions. for a typical run, what would take hours now takes a few seconds.

the results

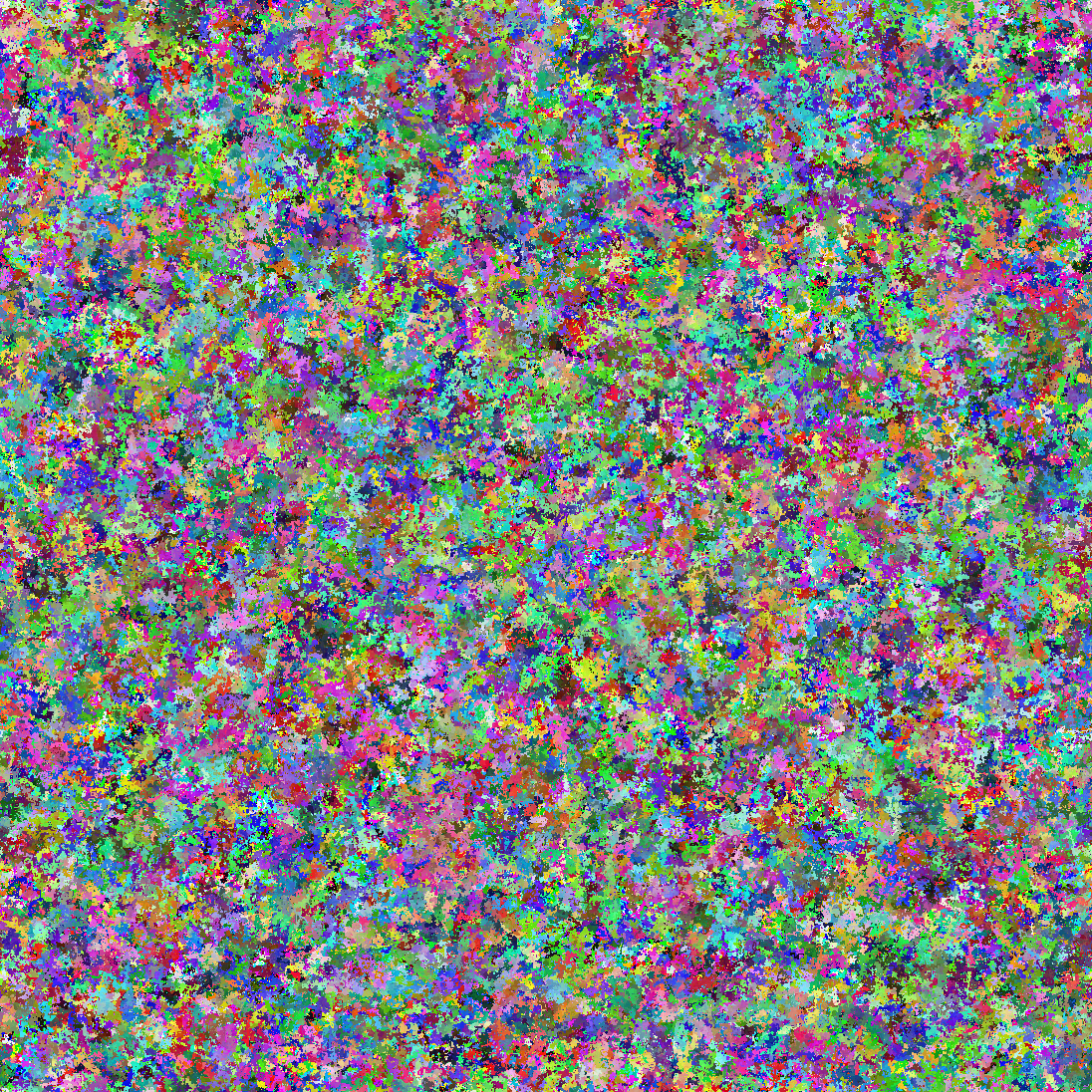

after implementing the generator, i ran it with different parameters, color spaces, and iteration counts. dense fills (200M iterations) create saturated, complex-looking patterns. sparse fills (10M iterations) leave more of the canvas visible, giving a lighter feel. different starting positions (random, center, corner) change how the color distributes across the image.

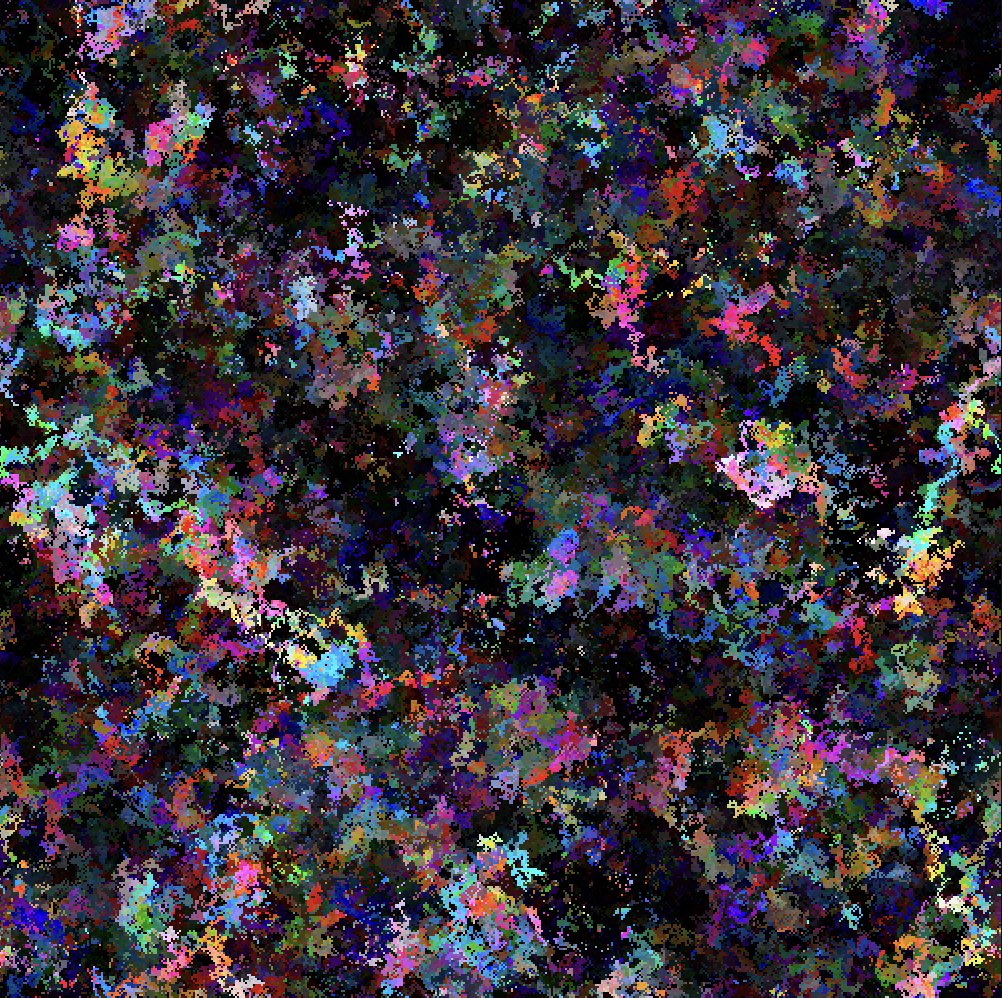

HSL, corner start, additive mode

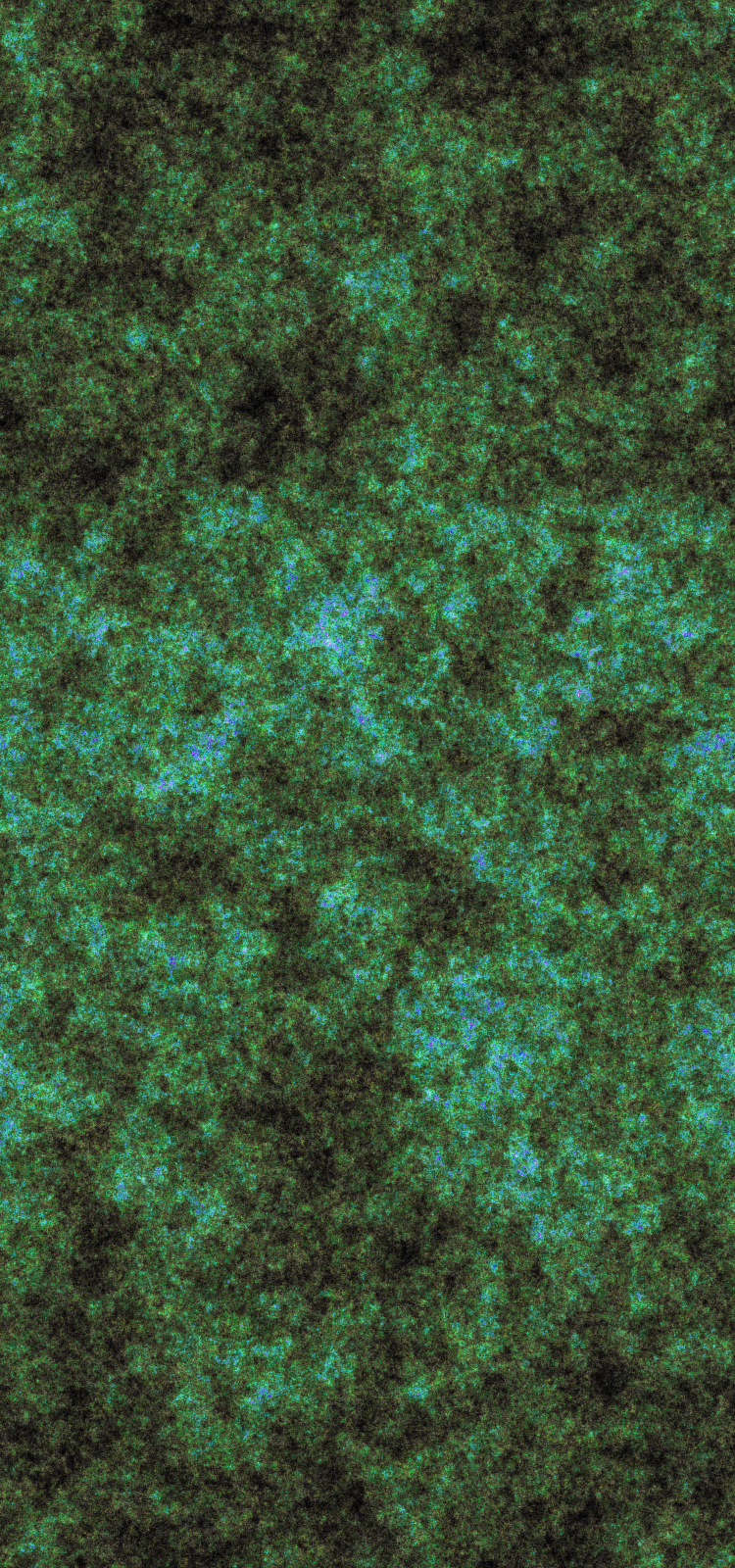

LAB, dense fill (200M steps)

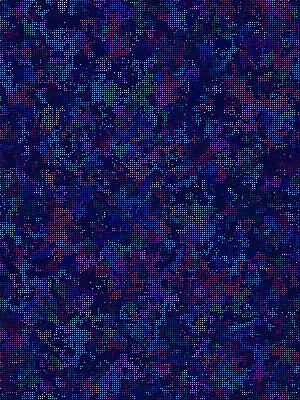

RGB, center start, dense fill

no two runs produce the same image. each is unique, but they share statistical properties. the \(\sqrt{n}\) scaling means the walk stays localized. the 2D recurrence guarantees it keeps revisiting areas, building up layers of color.

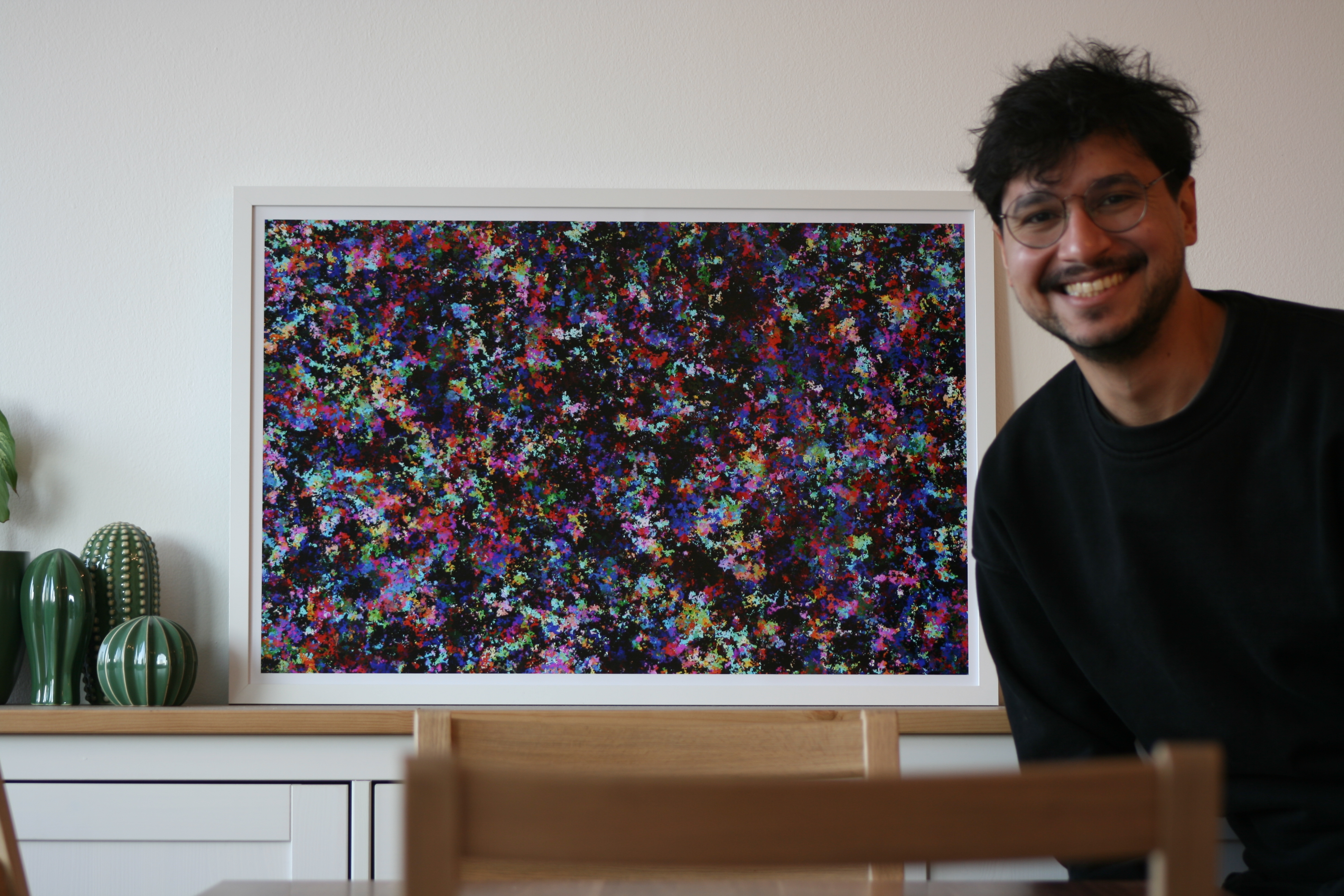

those empty walls? not anymore. printed it (i won't get into the details of the printing process, but it was a pain to get it right), framed it and put it there. now i have something i made myself, that i actually understand. every line, every color, every pattern. knowing the math doesn't ruin it, it makes it better!

the code is on github. feel free to install it, generate a few hundred images with different parameters (your CPU will thank you for the workout), pick your favorites, print them. the gallery script includes curated configurations to get you started. every run is different (as long as you change the seed). that's the point.