grpc & protobuf: efficient communication by design

i've spent enough time debugging microservice communication to appreciate what gRPC and protocol buffers bring to the table. when you're dealing with distributed systems, the way services talk to each other matters - not just for performance, but for sanity. this post digs into how they work under the hood and when they're actually worth using.

why rpc matters

once you break up a monolith, every function call becomes a network call. REST gave us a universal way to handle this, but it's not free: you're writing JSON by hand, parsing it on both ends, and keeping documentation in sync with code. i've seen too many bugs from mismatched field names or forgotten null checks.

RPC takes a different approach: you define your interface once, the compiler generates both client and server code, and you're done. gRPC takes this further with HTTP/2 for multiplexing, built-in streaming, and binary encoding through protocol buffers. the wire format is what makes it interesting from a systems perspective.

protobuf: the wire format

protocol buffers are schema-first, which means you write a .proto file and the compiler does the rest. what i find elegant about it is how the wire format works: it's compact, backward-compatible, and works across any language. this isn't just a nice-to-have, it's what makes protobuf practical for systems that survive the test of time.

1syntax = "proto3";

2

3message Person {

4 string name = 1;

5 int32 age = 2;

6 string email = 3;

7}

8

9message GetPersonRequest {

10 int32 person_id = 1;

11}

12

13message GetPersonResponse {

14 Person person = 1;

15 bool found = 2;

16}here's the clever bit: each field gets a numeric tag, and that's what actually goes over the wire, not the field names. no "user_id" strings repeated in every message, just a number. field numbers 1-15 take one byte to encode, 16-2047 take two. this matters when you're designing schemas for high-volume data.

how encoding works

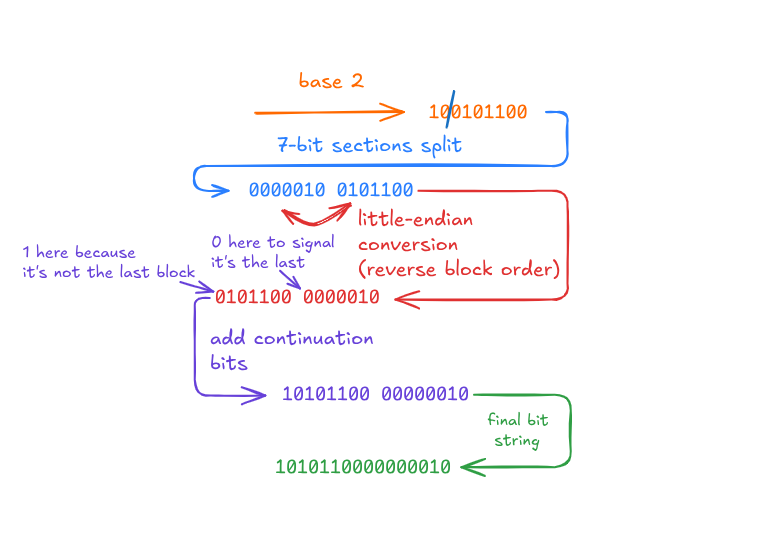

the encoding scheme is straightforward: tag-length-value. each field starts with a tag (field number + wire type), then optionally a length for strings or bytes, then the actual value. integers use varint encoding, which is where the size savings really show up for common cases.

varint encoding is simple: use the most significant bit as a continuation flag. small integers (0-127) fit in one byte. larger numbers take as many bytes as needed. most real-world data skews small (user IDs, counts, enums) so this saves space where it actually matters.

proto definition

message Person {

string name = 1;

int32 age = 2;

}data

{

"name": "alice",

"age": 28

}wire format breakdown

play with the interactive above to see the byte-by-byte breakdown. what i like here is how field tags pack both the field number and wire type into a single byte. it's compact without being clever to the point of pain. you can still mess with it with a hex dump and the spec.

size & performance

binary encoding cuts payload size. no field names repeated everywhere, no quotes, no whitespace. for high-throughput systems this does make a difference. the trade-off is obvious: you can't just curl an endpoint and read the response. debugging requires tooling, which can be annoying until you accept it.

JSON

{

"id": 12345,

"name": "alice",

"email": "alice@example.com",

"age": 28,

"active": true

}Protobuf

size comparison

the size wins compound with arrays and nested data. JSON repeats field names for every single object in an array. protobuf encodes the tag once per field, varints keep numbers small, and you're done. i've seen this cut metrics pipeline bandwidth by 60%. when you're paying for data transfer, that's real money!

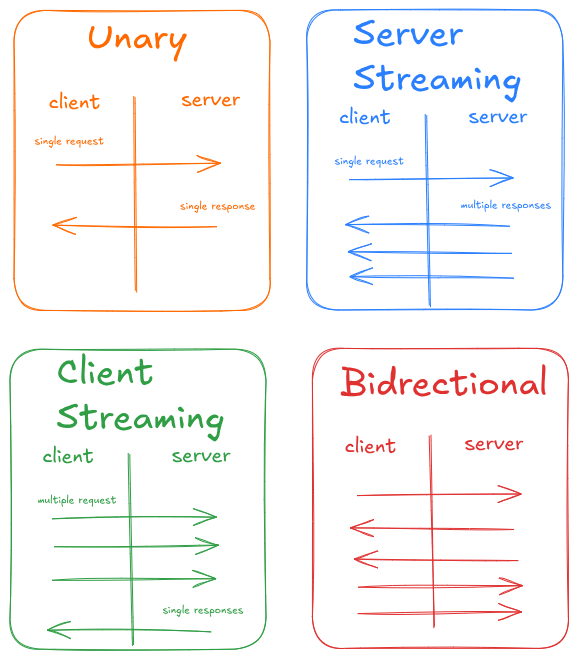

grpc mechanics

gRPC gives you four call patterns: unary (request/response), server streaming (one request, many responses), client streaming (many requests, one response), and bidirectional (streams both ways). all of this runs over HTTP/2, so you get multiplexing, flow control, and header compression without thinking about it.

1service UserService {

2 rpc GetUser(GetUserRequest) returns (GetUserResponse);

3

4 rpc ListUsers(ListUsersRequest) returns (stream User);

5

6 rpc BulkCreateUsers(stream CreateUserRequest) returns (BulkCreateResponse);

7

8 rpc ChatStream(stream ChatMessage) returns (stream ChatMessage);

9}streaming is where gRPC actually shines. server streaming works great for real-time feeds or pagination without loading everything into memory. client streaming fits batch uploads or continuous metrics. bidirectional handles things like chat or collaborative editing where both sides need to push data. once you have streaming, a lot of polling patterns just disappear.

code generation in action

code generation is the part that saves you months of work. define your service once, run the compiler, and you have type-safe clients and servers in whatever language you need. here's a python server and node.js client talking without any manual serialization. this is cross-language communication that actually works.

1# server.py

2import grpc

3from concurrent import futures

4import user_pb2

5import user_pb2_grpc

6

7class UserService(user_pb2_grpc.UserServiceServicer):

8 def GetUser(self, request, context):

9 if request.user_id == 1:

10 return user_pb2.GetUserResponse(

11 user=user_pb2.User(

12 id=1,

13 name="alice",

14 email="alice@example.com"

15 ),

16 found=True

17 )

18 elif request.user_id == 2:

19 return user_pb2.GetUserResponse(

20 user=user_pb2.User(

21 id=2,

22 name="bob",

23 email="bob@example.com"

24 ),

25 found=True

26 )

27 context.set_code(grpc.StatusCode.NOT_FOUND)

28 return user_pb2.GetUserResponse(found=False)

29

30 def ListUsers(self, request, context):

31

32 users = [

33 user_pb2.User(id=1, name="alice", email="alice@example.com"),

34 user_pb2.User(id=2, name="bob", email="bob@example.com"),

35 ]

36 for user in users:

37 yield user

38

39def serve():

40 server = grpc.server(futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=10))

41 user_pb2_grpc.add_UserServiceServicer_to_server(UserService(), server)

42 server.add_insecure_port('[::]:50051')

43 server.start()

44 server.wait_for_termination()

45

46if __name__ == '__main__':

47 serve()1// client.js

2const grpc = require('@grpc/grpc-js');

3const protoLoader = require('@grpc/proto-loader');

4

5const packageDefinition = protoLoader.loadSync('user.proto', {

6 keepCase: true,

7 longs: String,

8 enums: String,

9 defaults: true,

10 oneofs: true

11});

12

13const userProto = grpc.loadPackageDefinition(packageDefinition);

14const client = new userProto.UserService(

15 'localhost:50051',

16 grpc.credentials.createInsecure()

17);

18

19// unary call

20client.getUser({ user_id: 123 }, (err, response) => {

21 if (err) {

22 console.error('Error:', err.message);

23 return;

24 }

25 console.log('User:', response.user.name);

26});

27

28// server streaming call

29const stream = client.listUsers({});

30stream.on('data', (user) => {

31 console.log('User:', user.name);

32});

33stream.on('end', () => {

34 console.log('Stream ended');

35});the generated code handles all the serialization, transport, and connection pooling. we just have to write business logic. type safety comes from the compiler, not runtime validation. this kills an entire category of bugs when the client and server have different specs because someone forgot to update documentation.

when to use grpc

gRPC makes sense for internal microservices where you control both ends. the performance wins show up under load: high request rates, large datasets, or bandwidth-constrained environments. if you have systems in different programming languages (e.g. go talking to python talking to rust), the code generation alone justifies it.

- microservices mesh: when you have 10+ services talking to each other, the generated clients and strong contracts prevent drift

- real-time streaming: metrics pipelines, live updates, or anything that needs server push

- low latency requirements: binary serialization is faster to encode and decode than JSON parsing

- mobile clients: smaller payloads mean less battery drain and faster load times on poor networks

when not to use grpc

browser support is still not great, you need grpc-web plus a proxy. debugging is harder when you can't just read the payloads. for simple CRUD with low traffic, REST is less work and the simple and effective solution. if you're building a public API for third parties, most of them expect REST. don't make them deal with protobuf tooling if they just want to hit your API with curl.

- public APIs: REST is more accessible and discoverable

- browser-first apps: fetch API with JSON is simpler than grpc-web setup

- debugging-heavy development: when you're constantly inspecting payloads with curl or browser devtools

- simple request/response patterns: if you never need streaming and performance isn't a bottleneck. KISS!

the takeaway

gRPC and protobuf trade human readability for efficiency and type safety. they work well in high-throughput internal systems where you control both ends and performance matters. the wire format is elegant with a compact varint encoding, minimal overhead, and backward compatibility built in.

the right choice depends on your constraints. if you're building a microservices platform with teams using different programming languages, gRPC can save months of integration pain. if you're shipping a public API or a simple web app, REST is less friction. use the tool that fits the problem. the most impressive tech doesn't matter if it makes your system harder to operate and maintain.

if you want to go deeper, the protobuf encoding guide has the complete wire format spec, and the gRPC docs cover all four streaming patterns with runnable examples in every major language.